5 principles for service-oriented programming languages

TL;DR. Some principles are emerging for what one might call service-oriented programming languages. The principles are general, so they can help when thinking about code even when operating outside of these languages. A little demo of the code shown in this article can be seen in this video.

Introduction

The rise of cloud computing has thrown many developers into the world of developing software that consists of services: components that can be executed independently and then be composed by means of message passing. Microservices continue this practice by making each service “small”, in the sense that it is organised around business capabilities, and potentially developed by an independent team.

Developing (micro)service-oriented systems poses a challenge that motivated substantial efforts in the identification and dissemination of useful tools and design patterns, some new and some well-known. At the latest Microservices Conference (that is Microservices 2020 at the time of this writing), the people behind the programming languages Jolie and Ballerina teamed up to tell a story that takes this even further: some principles are so important for service-oriented programming that programming languages should consider supporting them natively.

—The banner of the conference Microservices 2020, which was held online due to the COVID situation.

—The banner of the conference Microservices 2020, which was held online due to the COVID situation.

In this article, I attempt at summarising some of these principles and the motivation behind them. You will also find a short video that applies these principles to a simple example.

The list of principles is by no means complete. More will follow. If you have an opinion on the principles listed here, what principles are missing, and how these principles related to existing technologies, I’d love to hear it!

The article consists of two main parts: motivation and principles. They can be read separately at different times, if you’re in a rush.

Motivation

Developing service-oriented systems is challenging for many reasons. Let’s revisit three of the main ones.

Integration. The problem of integration is pervasive in service-oriented systems:

- The services that we have to compose might be implemented with different languages or frameworks.

- A service might need data from an application that is not controlled by the service developers (this happens often when integrating legacy applications, or even with new ones in the context of microservices).

- To obtain a working system, services (and clients) need to coordinate with each other.

Dealing with these aspects can take a long time. We seem to be spending more and more time on integrating components rather than developing the components themselves. (In fact, some big consultancy companies might tell you that we’re now spending more time on integration than on anything else.)

Technical debt. The scenery of service-oriented computing is moving fast, and service-oriented systems easily fall prey to technical debt. For example, we might need to make our data available under a new format, or change the configuration of how our services can be reached. Technical debt is, by its very nature, easy to see with hindsight but very hard to predict. We should at least try our best to isolate and decouple the bits and pieces that are likely to change in the future from the code that implements the business logic of a service. However, working out what this decoupling should be and how it works is nontrivial.

Distribution. A very concrete example of technical debt is that we tend to fix assumptions on which components of an application will be distributed and which will run in the same executable. If you ever tried porting a monolith to a microservice architecture, you probably know the pain of revisiting these assumptions. Ideally, we should design components such that they could be grouped in the same executable or spread out over a cloud, but how should we go about this?

—Image by https://unsplash.com/@tvick.

—Image by https://unsplash.com/@tvick.

Principles of service-oriented languages

We now move to describing a few principles that can help us in dealing with the challenges above.

The principles are first presented by going through the design of a simple Greeter service, which clients can invoke to get back a greeting message. We keep the definitions of these principles purposefully generic. Later, we will reflect on their interpretation and utility.

The principles are general, so you could apply them to your own code, or you might create a framework for another language that supports them (some frameworks support a few of these principles). To map concepts to code as directly as possible, I’m going to develop the example and show how the principles are incarnated in the Jolie programming language.

In the Jolie development team, we chose the route of a programming language because it gives us a stronger tool for keeping developers on the right track. Languages influence how we think. If we want these principles to succeed, then we shouldn’t require developers to actively think about them. Rather, adopting the principles should be obvious and efficient. Also, the standard way of programming should be following the principles. Escaping the principles should be hard and make the developer doubt of their choices. These objectives are hardly achievable with a framework: we lose simplicity because we must learn how to use both the language that the framework is implemented in and the framework itself on top of it; and we can keep using other libraries or the bare features of the host language, which put us at risk of breaking the principles.

—The logo of the Jolie programming language.

—The logo of the Jolie programming language.

That said, let’s start visiting our concepts through the lens of our Greeter service example.

APIs

An API (Application Programming Interface) defines the contract between a service and its clients. An API should specify, at the very least:

- The data types that define the structures of the data that is going to be exchanged between the service and its clients.

- The operations that the service makes available to clients.

APIs are essential to service programming, since they allow us to check whether a service offers what we need while at the same time abstracting from how the service is concretely implemented. This brings us to our first principle.

Principle 1: formal APIs. Service APIs should be defined in a formal language, which is ideally technology agnostic, unambiguous, machine readable, and based on well-known abstractions.

Say that our Greeter service should receive client requests containing a name (the name of the person that we should greet), and send back a response that contains a greeting.

We can define these data types as the following record types.

type GreetingRequest { name:string } // The type of greeting requests

type Greeting { greeting:string } // The type of greetings

We can now use these data types to define an interface (Jolie for API) that specifies an operation greet that our service is going to offer to clients to obtain a greeting.

interface GreeterIface {

RequestResponse: greet( GreetingRequest )( Greeting )

}

Above, RequestResponse means that operation greet receives a request and always sends back a response to clients. (Jolie also offers OneWay as an alternative, meaning that the client does not need to wait for a response.)

We then define that greet expects requests of type GreetingRequest and sends back responses of type Greeting.

Observe that what we have written so far is technology-agnostic, in the sense that our data types correspond to types that would make sense in most technologies. This principle is somewhat present also in the interface languages of protocol buffers and OpenAPI. Some frameworks that used the Web Service Description Language supported binding XML data structures to other formats in HTTP messages.

Another important aspect when designing an API language with integration in mind is structural typing. If you are not familiar with structural typing, don’t worry: we’re going to revisit the concept later on. In a nutshell, this means that if a client and a service have defined their data types using different names or other details that do not matter when it comes to how data can be accessed, then these types should be deemed compatible.

Principle 2: structural typing. API languages should support structural typing.

Services

APIs are implemented by services, which are independently executable software artifacts.

Jolie provides a native keyword to define a service, called service.

For instance, we can start writing the implementation of a service Greeter, which will implement our GreeterIface API, by writing the code below.

service Greeter {

/* ... */

}

Principle 3: components are services. Components are services that can, in principle, be independently executed. Services should be clearly identifiable in source code. Ideally, the scope of their definition is clearly delimited, e.g., supported by structured programming constructs (as above) that can be used at will.

Access points

A service exposes its APIs to clients by means of access points, which define how the service can be reached by messages.

In Jolie, an access point is created by using the keyword inputPort. To define an access point, we must state:

- The location at which clients can reach the service.

- The transport protocol that clients should use to communicate.

- The interfaces (that is, the APIs) that can be accessed.

Each one of these components has a corresponding primitive in Jolie. Below, we define an access point that:

- Accepts connections on TCP port 8080.

- Uses HTTP as transport protocol, encoding data with the JSON format by default.

- Exposes the

GreeterIfaceAPI.

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

/* ... */

}

We introduce a principle for access points as well, which we are going to reflect on later.

Principle 4: decoupling of access points from business logic. The definition of access points should be separate from the implementation of the business logic of the service.

Behaviour (or business logic)

Now that we have defined an access point for our service, we have to code the behaviour that implements the business logic for the API that we are exposing.

Our API, GreeterIface, offers one operation, called greet. What we want to do is writing a behaviour that:

- Receives a message for

greet. In Jolie, this is done simply by writing the name of the operation. - Stores the received client request in a variable, say

request. - Computes a response containing a greeting, for example using a variable called

response. - Send the content of

responseback to the client.

To receive a message for an operation in Jolie, we just write the name of the operation, followed by the name of the variable where we want to store the request and the expression that should be evaluated to get the response, in parentheses.

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

// Behaviour of the service, or "business logic"

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

/* code for computing response based on request here */

}

}

}

In the curly brackets that go together with the input statement on greet, we can write the code that computes out greeting.

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

// Behaviour of the service, or "business logic"

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

}

}

}

Observe that our business logic implementation does not mention that request or response are encoded in the JSON format. In fact, as we are going to see, this implementation can work also with other wire formats without modifications.

Principle 5: abstract data manipulation. The implementation of business logic should, as far as possible, abstract from how data is represented on the wire.

Taking stock

Let’s take stock and have a look at the complete program that we got so far. We are then going to reflect on a few important aspects of how we have programmed it.

// Data types

type GreetingRequest { name:string } // The type of greeting requests

type Greeting { greeting:string } // The type of greetings

interface GreeterIface {

RequestResponse: greet( GreetingRequest )( Greeting )

}

// Service definition

service Greeter {

// Access point

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

// Behaviour of the service, or "business logic"

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

}

}

}

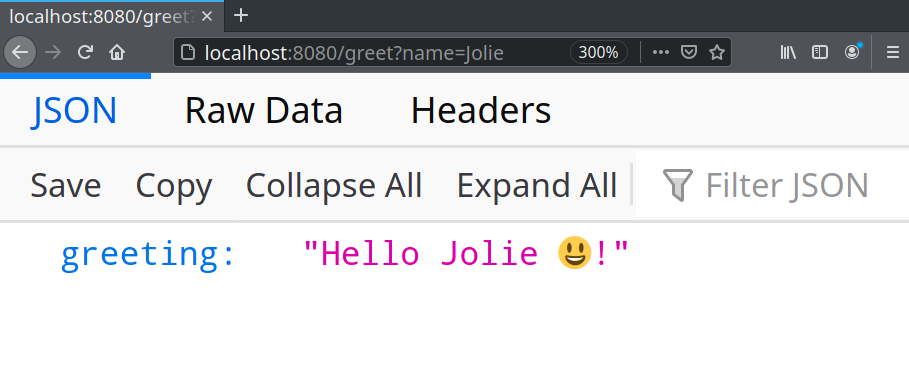

This is a complete Jolie program. You can store it in a file, say greeter.ol, and then launch it from the command line by executing the command jolie greeter.ol. Visiting the URL http://localhost:8080/greet?name=Jolie would then get you the following reply.

You can watch a brief live demo of the development of Greeter and its invocation in the video below.

Reflections on the principles

We now reflect on the usefulness of the presented principles.

Principle 1: formal APIs

Thanks to principle 1, it is possible to devise tools that can:

- Check whether the API of the service is compatible with what clients need.

- Generate API descriptions in other languages, like those in OpenAPI or WSDL.

These advantages are relevant for integrating services with other components and also for integrating with other technologies.

Principle 2: structural typing

Differently from many other languages, Jolie adopts a structural view on types: to determine whether two types are equivalent, Jolie looks at their definitions. This means that even if two services use two different names for the type of some data but the type structures are equivalent, then Jolie can tell that everything is OK.

Consider, for example, the following data type Team.

type Team {

name:string

description:string

}

Now, say that we tried to send a message of type Team to a service expecting something of the following type Group.

type Group {

description:string

name:string

}

The types Team and Group have different names and their definitions use a different ordering of the fields. But fields are unordered in Jolie, and names to not matter thanks to structural typing. So the communication would not incur a type error.

This kind of flexibility makes integration easier. It also allows Jolie to communicate easily with services written in other technologies, because the types of a Jolie service just need to be equivalent to those used by the other services, and not defined in the same language. Also, services can be developed a bit more independently, because we do not care about differences in details that do not matter.

Jolie has adopted structural typing since 2008. More recently, Ballerina uses structural typing as well.

Principle 3: components are services

Principle 3 aids the programmer in having code that corresponds closely to the intended model (a service, in this case), which makes us more effective.

Making it very easy to write many services can aid in dealing with technical debt and distribution. Say that we wanted to change Greeter to authenticate clients and get profile information, by using a separate component called UserProfiles (responsible for managing user profiles):

- In a language that is not service-oriented, we might be tempted to define that component as something that is not a service, which would then become an integral part of

Greeterthat is very hard to detach in the future. This technical debt could bite us in the future if we ever wanted to scale up and makeUserProfilesa service that can be run independently. - Differently, in a service-oriented language, we would be guided (Jolie would actually force us) to make

UserProfilesimmediately a service. Initially, we might decide to runGreeterandUserProfilesin the same machine, or even in the same process. But the principle leaves us free to distribute these services in the future, or even to make these services automatically redeployable (as in serverless). For this to work, it is important that:- The language discourages knowing whether another service is running in the same execution environment (e.g., a process in the operating system) or not.

- The language makes communications between services running in the same execution environment efficient.

Principle 3 thins the different between monoliths and microservice architectures: a monolith is a collection of services, and distributing it requires less effort. (See also non-distributed microservices.) We are going to give a concrete example of this at the end of the next section, by combining principle 3 with principles 4 and 5.

Principles 4 and 5: decoupling of access points from business logic and abstract data manipulation

Principles 4 and 5 are in synergy, so we discuss them together.

These principles help with getting code that can be reused with different data formats. For example, say that we wanted to send greetings encoded in XML instead of JSON. We just need to change the input port of Greeter to use xml as format, without the need for updating the implementation.

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

// Here we change format = "json" to format = "xml"

protocol: http { format = "xml" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

}

}

}

Since the business logic implementation abstracts from the concrete representation of data (principle 5), we do not need to change the code within the main block.

Another advantage is that we can define multiple access points to the same service. For instance, we could make our Greeter service available both through HTTP and a binary protocol (here we use SODEP, a binary protocol distributed with Jolie).

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

inputPort GreeterInputBinary {

location: "socket://localhost:8081"

protocol: sodep

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

}

}

}

Also in this case, reusing the same business logic implementation for both access points does not require updating the main block.

The last advantage brought by these principles that we discuss here is that they help with integrating code written with different technologies.

Since access points are defined separately from business logic implementations, we can write such implementations in different languages.

In Jolie, this is achieved with the keyword foreign. For instance, suppose again that our Greeter service needed a UserProfiles service that we want to implement in Java. We can achieve this by implementing a class greeter.UserProfiles that implements the necessary API as Java methods and then extending our example as follows (we omit the definition of the API of UserProfiles).

service UserProfiles {

inputPort UserProfilesInput {

location: "local://UserProfiles"

interfaces: UserProfilesIface

}

foreign java {

class: "greeter.UserProfiles"

}

}

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

outputPort UserProfiles {

location: "local://UserProfiles"

interfaces: UserProfilesIface

}

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

// Get the profile by invoking UserProfiles

getProfile@UserProfiles( request.credentials )( profile )

if( profile.ok ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

} else {

response.greeting = "Sorry, something went wrong"

}

}

}

}

(We keep error management simple here, but in the real-world you would want to have an explicit error case in the type of responses.)

The code above will run the service defined in Java as class greeter.UserProfiles and make its API available on the efficient local memory channel local://UserProfiles.

The construct outputPort used inside of Greeter enables the service to use the API of UserProfiles.

Assume now that we wanted to run UserProfiles as a service that runs remotely and is available at the address userprofiles:9090 using the binary protocol SODEP. We can simply reconfigure the output port of our Greeter service, without touching its business logic implementation.

service Greeter {

inputPort GreeterInput {

location: "socket://localhost:8080"

protocol: http { format = "json" }

interfaces: GreeterIface

}

outputPort UserProfiles {

location: "userprofiles:9090"

protocol: sodep

interfaces: UserProfilesIface

}

main {

greet( request )( response ) {

getProfile@UserProfiles( request.credentials )( profile )

if( profile.ok ) {

response.greeting =

"Hello " + request.name + " 😃!"

} else {

response.greeting = "Sorry, something went wrong"

}

}

}

}

Conclusion

We discussed some principles that have emerged (some are emerging) as important in the development of (micro)service-oriented systems. Not only do they bring advantages in isolation, but they also present significant synergies.

Some languages support a few of these principles natively, to make sure that developers can follow them effectively. Jolie supports all the principles that we discussed. WS-BPEL supports principles 1, 4, and partially 3 (only one service per program). Ballerina supports principles 2, 3, and partially 4 (references to external services are defined within the implementation of the business logic).

The list of principles that we have discussed is certainly not complete. There are other principles that, for example, have to do with deployment, observability, and reconfiguration. There are also features that become possible thanks to the principles that we have described, which we have not talked about here. For instance, Jolie exploits the combination of principles 1, 2, 4 and 5 to offer native primitives for architectural programming, which cover cases such as API Gateway and Circuit Breaker (a discussion can be read in this paper). These could be topics for future write-ups.